AS noted here yesterday, the statistics thrown around by those concerned that a workforce is lagging in education are sometimes misleading. In the case of my post yesterday, newly appointed UMaine President Sue Hunter made some curious remarks:

A part of it is when you look at educational attainment in New England … the rate of high school diploma earning in Maine is one of the highest in the country. We’re right up there with the top states. But then when you look at the associate degrees, bachelor’s degrees or graduate degrees, we are much lower. And even more significantly, we are much lower than the rest of New England.

When you look at economic development, the infusion of capital, influx of business, development of new business, it requires an educated workforce. It’s not that we don’t have good people, but they don’t have the skill set. And when you look around, you realize that the rest of New England is far ahead of us in those educational attainment metrics. That to me is important.

And as I noted:

[S]he suggests that Maine’s workforce does not have the educational attainment necessary to meet the demands of the state’s employers. Granting that assumption for the sake of argument, but then what does the supply of degree holders in the five other New England states have to do with the demands of Maine employers? In short; nothing.

It’s important to look at the nuances of the data being tossed out by pundits, policymakers and others regarding education/workforce development and job growth. In the case of Hunter, she is tryign to argue Maine’s workforce is lacking education and skills based on statistics that have little bearing on the Maine economy.

Now we turn to Eduardo Porter at the New York Times, writing recently about how increasing the education of the U.S. population will increase incomes (h/t to Matt Leichter for highlighting this). In making this argument, he suggests that the U.S. is lagging behind other nations in terms of education:

But in the American education system, inequality is winning, gumming up the mobility that broad-based prosperity requires. On Tuesday, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development released its annual collection of education statistics from around the industrialized world showing that the United States trails nearly all other industrialized nations when it comes to educational equality.

And the statistics Porter is referencing:

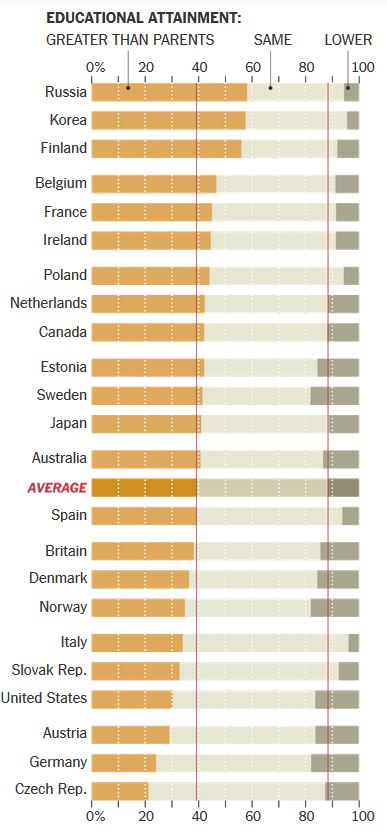

Barely 30 percent of American adults have achieved a higher level of education than their parents did. Only Austria, Germany and the Czech Republic do worse. In Finland more than 50 percent of adults are more educated than their parents.

Again, statistics are offered to support a claim of a workforce lagging in terms of skills and declining economic prosperity for workers. Basically, Porter argues that the U.S. needs to catch up to these other nations in terms of topping the educational achievement of the previous generation. Convincing? Hardly once we look at the chart that accompanies Porter’s statements:

Did you catch that? Russia leads in that metric, with Germany second from the bottom. As Leichter (sarcastically yet poignantly) writes:

The number one country is Russia, which is known for its healthy, long-lived population and very little national income from locational advantages such as oil and gas deposits. Second to last is Germany, a country with very few manufacturing exports and unspeakable squalor, which is why you never hear about it . . . Like seriously, read your own damn chart.

Game, set, match, Leichter.

Expanding on that, there are other problems with Porter’s argument; namely that according to the OECD report his piece is predicated on, the U.S. ranks 5th in percentage of 25-64 year olds with a college degree. Interestingly, Russia ranks first while Germany 23rd and below the OECD average.

However, Porter’s argument that education equals higher incomes, and he presents the U.S. as lagging in terms of educational attainment, then we should expect the U.S. to lag in terms of income. We don’t. As of 2012, the U.S. led all OECD countries (which does not include Russia) in terms of average wages. Obviously average wages are fallible, and inequality in the U.S. exceeds that in countries like, say, Germany . . . but want to guess the state of wages and inequality in Russia, the number one country on Porter’s list, relative to the U.S. and Germany?